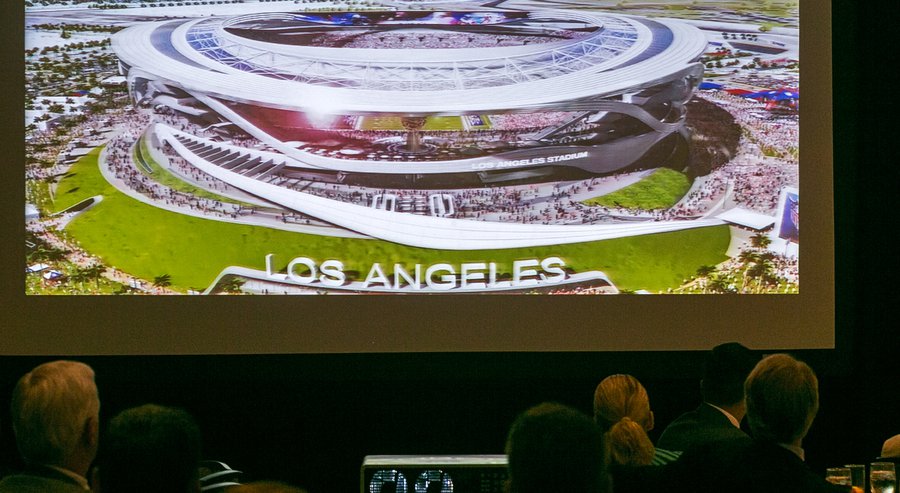

Now, it’s 2015, and on January 12 and 13th in Houston, the NFL Owners will consider the idea of approving either one or two existing teams to move from Oakland, San Diego, or St. Louis, and to the Los Angeles Region, and in Carson or Inglewood, California. Thus, continuing what seems to be a sisyphean task in putting an NFL team there.

Considering that the NFL has not had a presence in LA since the Rams and Raiders left in the mid-90s, one would think there would be keen interest in not just how much either stadium proposal in Carson or Inglewood would cost, but how construction of them would be paid for. The fact is as much a statement on the state of media today as anything else: there’s precious little focus on the subject by reporters, columnists, or bloggers.

So, given that my background is urban economics, planning, and public finance, and my first job out of grad school at Berkeley was with the Oakland Redevelopment Agency, not to mention starting my own economic consulting firm, not to mention working for two of the last five mayors of Oakland. Not to mention forming the bid to bring the Super Bowl to Oakland, and not to mention then starting a company around an online game I made where one could run the business of the Oakland Athletics (and was used in 40 colleges and high schools in America), I decided to make a spreadsheet of how the Carson stadium financing sources and uses look based on the information I collected and that I could find online and from conversations I’ve had with a number of sources about it.

To cut to the chase, the spreadsheet I formed and is visible here reveals that if the stadium costs $2 billion, there would be a thin revenue surplus of $163 million. The problem is the more that’s done to achieve a cushion to guard against cost overruns (and $163 million is not a good cushion, where $300 million would be) the higher the price for tickets, suites, and seat licenses have to be – and the higher they have to be, the more likely it is they all won’t sell.

And when it happens that stadium PSLs and luxury suites don’t sell well, you’re looking at a potential for default on bonds floated for the Carson project. (For those of you who are saying “It’s cool, Goldman Sachs has our back because they’re doing the financing,” the fact is, no one wants a situation that could result in the stadium being owned by, and potentially liquidated by, the bond trustee – that would be it.)

The Chargers, Raiders, and the NFL seem to be working in cheerful ignorance of one apparent fact: the palaces planned for LA will price out current Oakland Raiders fans, and (to some degree not analyzed here) San Diego Chargers fans. Keep reading, please.

The reasons start with the cost of the stadium itself. Some will complain that the cost is really $1.7 billion and not $2 billion. But the problem is the cost of the Carson facility was first said to be just over $1.6 billion, then it was just over $1.7 billion. Research (http://www.stadiummouse.com/stadium/economic.html) shows that stadium cost overruns are historically at the least 40 percent over estimates and one expert has said that as much as $500 million in change orders are applied to a common, new NFL stadium in the 21st Century. Considering that information, I can make an argument that when all is said and done, the Carson stadium will cost $2.3 billion, but I’ll stick with $2 billion.

Let’s add more perspective: at $2 billion, the Carson NFL Stadium will be $400 million more than the current most expensive NFL Stadium, MetLife Stadium in New Jersey. It will cost almost as much as all of the new NFL stadiums built in the 90s. Moreover, it will have 202 luxury suites, and a base of 65,000 seats, versus 220 luxury suites and 84.000 seats for MetLife Stadium – that’s called getting less for more, and a lot more at that. How does one pay for that?

One answer is having two NFL teams use the stadium as co-tenants – all the better to generate money for lease revenue serial bond issues floated by the new Carson Stadium Authority. The New York Jets and New York Giants have this arrangement at Metlife Stadium, and have enjoyed such a nice relationship with the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority, and many New York and New Jersey elected officials, that even sales taxes normally applied to the sale of tickets and luxury suites were waved.

In the Carson case, it’s not clear Carson Holdings LLC boss Carmen Policy and Disney CEO Bob Iger have that kind of juice with Carson or with LA County or for that matter with California Governor Jerry Brown as of this writing. Indeed, the Carson stadium is touted as entirely privately financed, which really means no obvious large government subsidy – such a tax break as was given for Met Life Stadium actually counts as a public subsidy. But. I digress.

What the two teams add to the total Carson financing picture in my spreadsheet are the following:

1) Naming Rights Sponsorship set at $400 million. And the reason for this, and not for $700 million, is it’s not clear Farmers Insurance is going to turn around and re-commit such a high dollar amount to an NFL LA stadium, again.

Farmers Insurance placed a bet based purely on faith in the entertainment company AEG and nothing else, and while Famers did enjoy some visibility, in the end, it got nothing in return other than being historically tied to another failed try at building a stadium in Los Angeles. $700 million is a gargantuan number that should have ignited the effort, but did not.

That cautionary tail is the reason there’s no deal at this time the third time around. Moreover, I personally doubt more than $400 million will be obtained this time. If the deal looks real, perhaps $500 million or $600 million, but I’m going to err on the conservative side, and again that’s because as of this writing, and even considering how far the Carson project has progressed, Farmers Insurance has not stepped back to be involved and no other firm has either.

The other consideration is how much of that will be used for stadium construction. Early on, the NFL’s Grubman was not warm to the idea of naming rights revenue being used mostly for building the facility, and the percentage tends to vary from deal to deal, so I elected to use 50 percent of the $400 million, or $200 million. That is more than I used in my Oakland Coliseum Reboot Spreadsheet (30 percent) and the reason was that the size of the stadium cost dictated I get as much as was reasonably possible. The point here is that a giant cost tends to mean that a larger percentage of a particular revenue stream must be used to pay for it – that’s money out of the team’s pocket.

2) Annual rent, which has not been discussed to this point, of $1 million, each. So, that annual rent times two teams, and for a 30 year bond issue period, comes to $60 million.

3) Sponsorships, which also have not been talked about to this point in the Carson project, I peg at $50 million in the spreadsheet and that’s separate from naming rights. How much would be used for stadium construction is also not known, and tends to vary with each NFL stadium deal, so I’m grabbing 50 percent of that, or $25 million.

4) The NFL G4 Loan programs presents a scenario where having two teams in one stadium becomes a clear stadium financing advantage over one team. Here, where one team can draw $250 million in league assistance, we double that to $500 million for the Carson NFL stadium. (And regarding the NFL payback period, it can be waived at league choice.)

5) Carson Stadium Luxury Suites are sold not once, but twice: for the Raiders games and for the Chargers games. While prices for the boxes have not been quoted, the planned number of them has, to this date: 202. While some will balk at this number, I’m pegging the average price at $200,000 and for this reason: no good market study has focused just on luxury suites in the Carson Stadium plan, moreover, no study has been done with respect to either specific team and what their fans will pay. At least as of this writing. I’d love to see it. At any rate, the total revenue here is $873 million over 30 years, or 36 percent of the total revenue from this source is used for stadium construction, versus 100 percent of PSL revenue used for stadium construction.

6) Seat Option Revenue is also a revenue advantage of having two teams in one stadium. In Carson, the Chargers and Raiders would have separate PSLs, but from the looks of the survey that was done in 2014, just one cost: high – the highest in the NFL if done. Questions from the survey and reported by many media outlets point to PSL cost as high as $50,000, and which points to a weighted average average cost of $15,000 and what I used in the spreadsheet. So, for two teams, that clocks in at a total of $600 million.

So we see a pattern emerging: the Carson stadium financing counts, to some extent, on a financing base that, in turn, rests on costs so high and never before done in Los Angeles, that, at the end of the day, it’s really an article of faith to believe this approach will work perfectly. And, we are talking about the LA Basin, where, while the unemployment rate has fallen from around 7 percent to 5 percent, the underemployment rate is 24 percent, and the highest in America. The underemployment rate reflects those who are employed but at a wage lower than it takes to make a reasonable living. A growing American economic problem.

On top of that, the LA Basin is ranked number 17th in per capita gross metropolitan product of roughly $61,000 versus $120,000 for San Jose and $103,000 for San Francisco in the SF Bay Area.

7) Finally, for revenue from conventions and meeting rooms annually, I assumed $20 million of that, 50 percent used for stadium construction, or $10 million.

In the end, I added bond issue expenses to the stadium total cost of $2 billion, or $2.272 billion and that’s versus $2.435 billion in total revenue for stadium construction. Again, that’s a $163 million surplus, or about just under 5 percent of the total cost. So while $163 million looks like a number you can live with, I can’t at all: it’s too small for comfort in having enough extra money to guard against the Carson deal not paying for itself. And, to repeat my point of earlier, creating more of a cushion in the spreadsheet means a higher price in it – it’s easy to just do that when you don’t have a real person paying the bill.

In my Oakland Baseball Simworld classroom model that I created and then refined with the help of Dan Rascher at the University of San Francisco, and was used by the University of San Francisco, as well as Georgia State and other schools (http://www.sportsbusinesssims.com/oaklandsim.htm), I designed in a price elasticity and a won-loss factor to discourage students from jacking up ticket prices just to have their team stay in the black for a given year. I think the Carson NFL Stadium deal developers would benefit from just such a regulator. Right now, the media will not question the ability of this deal to work – instead, it will stick in its own assumptions about LA and based on a region of 25 years ago, not today.

The LA Basin of today is losing entertainment jobs to places like Georgia (and in particular, Atlanta) and Virginia, and in the process of developing a tech community that is in no way the rival of the San Francisco Bay Area. The defense industry there, when it hasn’t moved to the Southwest, has lost contracts to overseas competitors. What the LA Basin has going for it, still, is population size – but the wealth some think it still has is largely a thing of the past. I can’t believe the NFL’s not aware of this to some degree, and it may be why it was rumored to have went to the NFL Players Association to seek help in paying for a stadium in LA.

What I wrote in analyzing Carson also applies to Inglewood, save for the use of development revenue. If that proposal has something like a hotel as part of the revenue used for stadium construction, then it would have a better cushion than in Carson. But that’s a guess. And anyone who thinks, at this point, that Stan Kronke is just going to “write a check” to quote some sports radio personalities, and because he’s a billionaire, does not know what they are talking about.

Ask Kronke. Ask Grubman.

If I were NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, I’d put this question to the NFL Owners: “What real gain do we realize in basically causing three of our teams to dump their current fan bases for the historically fickle and currently untested people and place that is the LA Basin? Can any Raiders fan hope to be able to afford to see their team in Los Angeles, given what is being proposed? Can a ‘Black Hole’ form? Will Chargers fans really try and buy into what is being proposed? And what do we lose from this? What do we get from it?”

I don’t know what Roger really thinks, but my view is this is too high a price to return to LA. The NFL has to understand that sometimes you just can’t go home again, and that the home you’re in isn’t so bad after all.

Stay tuned.

Carson NFL LA Stadium Basic Spreadsheet by Zennie AbrahamCarson La Stadium by Zennie Abraham

Zennie Abraham | Zennie Abraham or “Zennie62” is the founder of Zennie62Media which consists of zennie62blog.com and a multimedia blog news aggregator and video network, and 78-blog network, with social media and content development services and consulting. Zennie is a pioneer video blogger, YouTube Partner, social media practitioner, game developer, and pundit. Note: news aggregator content does not reflect the personal views of Mr. Abraham.